Why Math Might Be The Secret To School Success

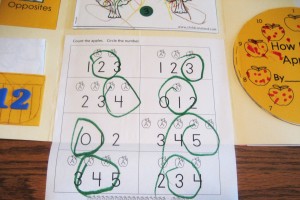

By Anya Kamenetz, NPR Little children are big news this week, as the White House holds a summit on early childhood education December 10. The President wants every four year old to go to preschool, but the new Congress is unlikely to foot that bill. Since last year, more than 30 states have expanded access to preschool. But there’s still a lack of evidence about exactly what kinds of interventions are most effective in those crucial early years. In New York City, an ambitious, $25 million dollar study is collecting evidence on the best way to raise outcomes for kids in poverty. Their hunch is that it may begin with math. Time That Counts “One! Two! Three! Four! Five!” Gayle Conigliaro’s preschool class are jumping as they count, to get the feeling of the numbers into their bodies–a concept called “embodied cognition.” P.S. 43 is located in Far Rockaway, Queens, just steps from the ocean. The area is still recovering from Hurricane Sandy. But now it’s been chosen as one of 69 high-poverty sites around New York City for a research study to test whether stronger math teaching can make all the difference for young kids. The study is funded by the Robin Hood Foundation, which is dedicated to ending poverty in New York. Pamela Morris, with research group MDRC, is lead investigator. “MDRC and the Robin Hood Foundation developed a partnership really with a broad goal,” she says, “Which is, they want to change the trajectories of low income children. And to do so by focusing on preschool.” There’s plenty of evidence on the long-term importance of preschool. But why math? Morris says that a 2013 study by Greg Duncan, at the University of California, Irvine, showed that math knowledge at the beginning of elementary school was the single most powerful predictor determining whether a student would graduate from high school and attend college. “We think math might be sort of a lever to improve outcomes for kids longer term,” Morris says. But there’s a real lack of math learning in pre-K. In one study, in fact, just 58 seconds out of a five-hour preschool day was spent on math activities. Part of the problem, says Doug Clements, at the University of Denver, is that “Most teachers, of course, have been through our United States mathematics education, so they tend to think of math as just skills. They tend to think of it as a quiet activity.” Clements is the creator of Building Blocks, the math curriculum being tested in this new study. Building Blocks is designed to be just the opposite: engaging, exciting, and loud. “We want kids running around the classroom and bumping into mathematics at every turn.” At P.S. 43, math games, toys, and activities are woven through the entire day. At transition time, the teacher asks the students to line up and touches their…

Read More »Questions Before Answers: What Drives a Great Lesson?

via Edutopia Recently, I was looking through my bookshelves and discovered an entire shelf of instruction books that came with software I had previously purchased. Yes, there was a time when software was bought in stores, not downloaded. Upon closer examination of these instruction books, I noticed that many of them were for computers and software that I no longer use or even own. More importantly, most were still in shrink-wrap, never opened. I recalled that when I bought software, I just put the disk into the computer and never looked at the book. I realized that I did the same when I bought a new car — with one exception. I never read the instruction book in the glove compartment. I just turned on the engine and drove off. I already knew how to drive, so I didn’t need a book. The exception occurred when I tried to set the clock. I couldn’t figure it out, so I finally opened the glove compartment and checked the book. This pattern was and is true for every device I buy. I never read the book that comes with a toaster, an iPod, or a juicer unless I have a question. There are some people who do read instruction books before using a device, but with no disrespect intended, those people are a small minority. Our minds are set up to not care about answers unless we have a question. The greater the question, the more compelling it is, the more we want the answer. We learn best when questions come before answers. The Need to Know Too many classrooms ignore this basic learning model. They spend most of class time providing information and then ask questions in the form of a quiz, test, or discussion. This is backward. Too many students never learn this way. It is simply too hard to understand, organize, interpret, or make sense out of information — or even to care about it — unless it answers a question that students care about. Lessons, units, and topics are more motivating when they begin with a question whose answer students want to know. Not only do great questions generate interest, they also answer the question that so many students wonder about: “Why do I have to learn this?” Finally, great questions increase cognitive organization of the content by framing it into a meaningful answer to the opening question. There is a catch, though, in using questions to begin your lesson. The question must be connected to the content, so that the following learning activities actually answer the question. The question must fit your students’ age, ability, and experiences. In addition, the question needs to provoke both thought and curiosity. In fact, it must be compelling enough to generate so much motivation so that students can’t help but want to know the answer. Have you ever forgotten the…

Read More »5 Open Education Resources for K-5 Common Core Math

From Edutopia There is an abundance of math open educational resources on the Web. So many, in fact, that Education Week asked, “Why is There More Open Content for Math than English?” Common Core is driving a lot of the growth in open education production and curation, with new databases and sources popping up left and right. It can be overwhelming to wade through everything, and find a source that works for your classroom. With that in mind, here are some math open education resources for elementary educators. A Few More to Check Out Khan Academy Common Core Map: It’s a challenge to find specific lessons that align with Common Core proficiencies. Khan Academy’s Common Core Map takes the guess work out that, providing an overview of processes and proficiencies with links to their aligned, web-based lessons. Khan’s Common Core resource page is another great source. Share My Lesson Common Core Database: Share My Lesson hosts an extremely comprehensive collection of aligned lesson plans from a variety of sources. Not only are lessons broken down by process and proficiency, they’re all free and there’s a huge number of them from favorite sources like Sesame Street. (Note: Using Share My Lesson does require signing up for a free membership.) Free Lessons from K-5 Math Teaching Resources: This is another site that has taken the guess work out of finding Common Core process-aligned resources. Here, you’ll find a comprehensive pool of K-5 math resources organized by grade level, and all are available as PDF download. Teaching Channel Common Core Video Series: The Teaching Channel’s videos provide an amazing in-classroom look at the Common Core in practice. For grades K-5, Teaching Channel has produced more than 70 videos, covering both math and English lessons. You’ll also find some great overview videos that will help answer general questions about implementing the new standards. Free Lessons from LearnZillion: I’ve written about LearnZillion before, but I’ve included their open ed resource database in this list, because it features some valuable Common Core-aligned math lessons for grades 2-6. Not to mention, this is a growing website, so expect more 2-6 lessons in the future, as well as kindergarten and first-grade resources. “ 5 Tips for Explaining Common Core to Parents,” by Kristen Swanson, THE Journal “Common Core Webinar: Assessment Shifts,” from Sue Brookhart, ASCD “Resources for Understanding the Common Core Standards,” from Edutopia Staff 6 Math Apps that Support Common Core State Standards, by Dave Wiggler,…

Read More »Why Do Americans Stink at Math?

New York Times By ELIZABETH GREEN When Akihiko Takahashi was a junior in college in 1978, he was like most of the other students at his university in suburban Tokyo. He had a vague sense of wanting to accomplish something but no clue what that something should be. But that spring he met a man who would become his mentor, and this relationship set the course of his entire career. Takeshi Matsuyama was an elementary-school teacher, but like a small number of instructors in Japan, he taught not just young children but also college students who wanted to become teachers. At the university-affiliated elementary school where Matsuyama taught, he turned his classroom into a kind of laboratory, concocting and trying out new teaching ideas. When Takahashi met him, Matsuyama was in the middle of his boldest experiment yet — revolutionizing the way students learned math by radically changing the way teachers taught it. Instead of having students memorize and then practice endless lists of equations — which Takahashi remembered from his own days in school — Matsuyama taught his college students to encourage passionate discussions among children so they would come to uncover math’s procedures, properties and proofs for themselves. One day, for example, the young students would derive the formula for finding the area of a rectangle; the next, they would use what they learned to do the same for parallelograms. Taught this new way, math itself seemed transformed. It was not dull misery but challenging, stimulating and even fun. Takahashi quickly became a convert. He discovered that these ideas came from reformers in the United States, and he dedicated himself to learning to teach like an American. Over the next 12 years, as the Japanese educational system embraced this more vibrant approach to math, Takahashi taught first through sixth grade. Teaching, and thinking about teaching, was practically all he did. A quiet man with calm, smiling eyes, his passion for a new kind of math instruction could take his colleagues by surprise. “He looks very gentle and kind,” Kazuyuki Shirai, a fellow math teacher, told me through a translator. “But when he starts talking about math, everything changes.” Takahashi was especially enthralled with an American group called the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, or N.C.T.M., which published manifestoes throughout the 1980s, prescribing radical changes in the teaching of math. Spending late nights at school, Takahashi read every one. Like many professionals in Japan, teachers often said they did their work in the name of their mentor. It was as if Takahashi bore two influences: Matsuyama and the American reformers. Takahashi, who is 58, became one of his country’s leading math teachers, once attracting 1,000 observers to a public lesson. He participated in a classroom equivalent of “Iron Chef,” the popular Japanese television show. But in 1991, when he got the opportunity to take a new job…

Read More »Repetition Doesn’t Work: Better Ways to Train Your Memory

via The Daily Beast A team of scientists recently discovered that repetition is a terrible way to memorize information—and their findings highlight much better strategies. A new study published in Learning and Memory found that simple repetition interferes with the ability to learn new information, especially when it is similar to a set of familiar facts. This may mean that memorizing facts about an issue through repetition could interfere with the ability to remember a more nuanced version of the same issue later on. “Our findings suggest that although the ability to generally recognize something is strengthened with multiple encounters, one’s ability to discriminate among similar items in memory decay,” the study says. “In contrast to past beliefs, repetition may reduce the fidelity of memory representations.” In study, subjects said a list of objects either one or three times. Later on, in the recall phase, another set of similar objects (“lures”) was snuck in. Those who had seen objects multiple times better recalled the original objects but had a harder time distinguishing the lures. In other words, their memories were stronger but less precise. Over the long run, repetition can be a false temptress, making us think we’ve learning something when we really haven’t. “On your first reading of something, you extract a lot of understanding. But when you do the second reading, you read with a sense of ‘I know this, I know this,’”explain psychologists Henry Roediger and Mark McDaniel, authors of Make it Stick. “So basically, you’re not processing it deeply, or picking more out of it. Often, the re-reading is cursory—and it’s insidious, because this gives you the illusion that you know the material very well, when in fact there are gaps.” Here are a few tips for better memory: Pace your studying Not all repetition is bad. It’s more accurate to say that cramming is ineffective. “The better idea is to space repetition. Practice a little bit one day, then put your flashcards away, then take them out the next day, then two days later,” explain McDaniel and Roediger. Repetition can be a false temptress, making us think we’ve learning something when we really haven’t. Mentally testing yourself on materials generally increases recall days later, even if there’s no feedback on how well you actually remember the facts. In other words, just going over the material in your head at regular intervals has benefits. Within academia, there’s a raging debate about the optimal spacing between recall intervals [PDF]. One of the original systems, by foreign language learning icon Paul Pimsleur, advocated for a pacing of five seconds, 25 seconds, two minutes, 10 minutes, one hour, five hours, one day, five days, 25 days, four months, and two years after the facts are initially learned. Since then, others have found that a slight delay of 10 minutes in the first retrieval made the task just mentally…

Read More »27 Ways To Increase Student Engagement In Learning

Student engagement in learning is kind of important. No matter the best practices of your curriculum mapping, instructional strategies, use of data for learning, formative assessment, or expert use of project-based learning, mobile learning, and a flipped classroom, if students aren’t engaged, most is for naught. Historically, student engagement has been thought of in terms of students “paying attention”: raising hands, asking questions, and making eye contact. Of course, we know now that learning can benefit from learner self-direction and self-initiated transfer of thinking as much as it does simple “engagement” and participation. That being said, increasing engagement and sheer participation is not a wrong-headed pursuit in and of itself, and in pursuit of that is the following infographic from Mia MacMeekin: 27 ways to increase student engagement. Divers diseases can affect the muscles that can slow the flow of blood, cause erectile dysfunction. Currently more than half of men aged over 50 reported some degree of erectile dysfunctions. A general sexual appeal among men is the erectile dysfunction. Now many articles were published about http://finasteride.me/. Our article tell more about the evaluation of erectile disfunction and “finasteride“. Questions, like “finasteride drug“, are linked variant types of soundness problems. Keep reading for a list of drugs that can cause side effects and what you can do to put an end to feasible side effects. Sometimes medical conditions or other medicaments may interact with Viagra. Before buying this generic, tell your physician if you are allergic to…

Read More »

Judo Math motivates all students to take responsibility. There are no ability groups, just pacing groups. By the end of each discipline, everyone is a black belt rank, reinforcing the unity of the class.

Judo Math motivates all students to take responsibility. There are no ability groups, just pacing groups. By the end of each discipline, everyone is a black belt rank, reinforcing the unity of the class.  www.capjax.com

www.capjax.com